By Philip C. Johnson

November 1, 2025

I was in Paris on November 13, 2015, waiting for a student group that would not arrive the next day—for obvious reasons. The 13th had felt ordinary; I walked the charming streets of Paris, the city alive with the usual Friday-night hum. By the time I had returned to my hotel, the night fractured. Sirens everywhere, my phone buzzing with frantic texts, the television looping the same impossible images: the Bataclan, the cafés, the stadium. One hundred thirty dead. Paris, still raw from the Charlie Hebdo killings ten months earlier, had been struck by ISIS, the militant jihadist group, again.

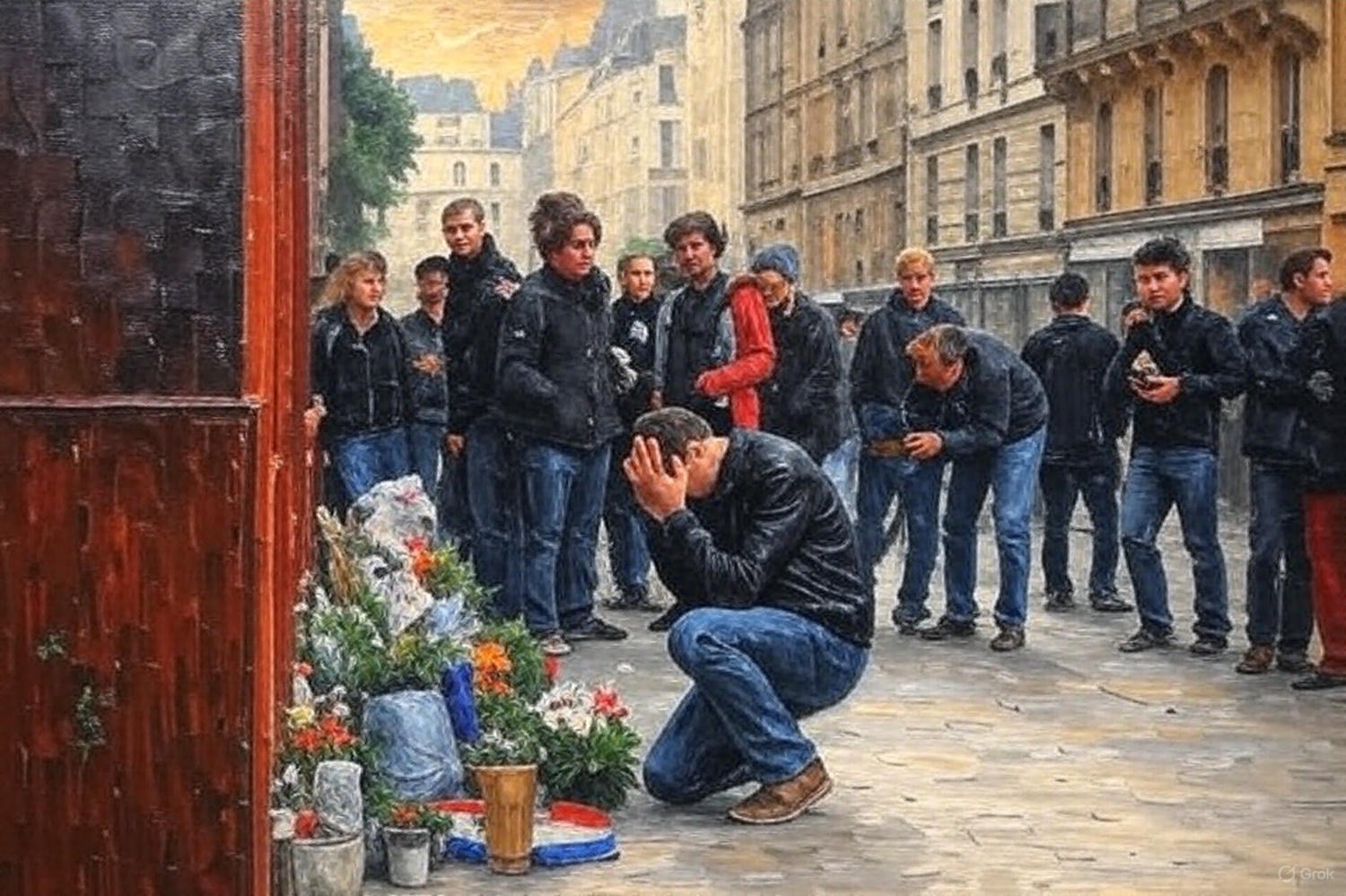

The following morning, I went to stand outside the theater where 90 people had been murdered. Flowers already piled against the bullet-pocked façade, strangers looking completely lost in the cold, police tape fluttering like surrender flags. Their shock mirrored my own: the sense that the ideology that brought this kind of violence—so up close and personal—did not belong in a city that had always treasured the exchange of ideas.

That was the Paris I carried into my first meeting with Arthur Dénouveaux, a few weeks ago, to discuss an event that changed his life a decade ago.

Ten years ago, on November 13, 2015, Arthur stood in the pulsing heart of the Bataclan theater, swaying to the carefree riffs of an Eagles of Death Metal concert. The air was thick with joy, young voices singing in unison, the crowd a tapestry of laughter and connection. “It was a very normal rock and roll show,” Arthur recalls, his voice steady but tinged with the weight of memory. Then, in a heartbeat, the melody died. “Everyone was singing along one second before, and then everyone was yelling one second after. That was the big difference.”

Arthur—alone that night, his wife of a year and a half at dinner with friends—removed his earplugs at the first crack. He thought it was the PA system failing. “I realized that was the sound of automatic rifles… maybe fifteen meters away… I see fire coming out of a rifle.” He dropped to the floor amid the collective scream, the crowd’s surge pinning him down. “Don’t stand up, or you’re gonna get shot. Don’t stay here, or you’re gonna get shot.” His nine months of mandatory military training kicked in: crawl, stay low, no heroics.

For five to ten minutes he inched across a churning mass of bodies. “It felt like a moment that did not belong to me,” he says, describing the surreal eternity of crawling toward an emergency exit he knew from a hundred prior concerts. “I crawl across people, and bodies, that were motionless… people who stood up trampled on me… I remember seeing—just before really reaching the streets—a guy at the bottom of some stairs… whose neck made an angle that seemed impossible, I was pretty sure he was dead.” A trial map later placed a cross exactly at that spot. One of the 90.

Emerging through the emergency exit, he hit the street still hearing gunfire and the dull boom of a terrorist’s vest detonating on stage. No sirens yet. No police. Just the cold night and the drummer of Eagles of Death Metal standing lost on the pavement, speaking no French. “He seemed even more lost than me… the guy doesn’t speak a word, he’s on stage and he sees people getting shot.” Arthur gathered the four band members, sprinted three minutes to Boulevard Voltaire, flagged two cabs, and only then—inside the second taxi—felt the first exhale of safety.

The Bataclan attack, part of a coordinated assault across Paris that claimed 130 lives, (more than 400 wounded) left an indelible mark on Arthur. In the days that followed, he returned to work two days later, only to be ambushed by a panic attack in a crowded subway. “Too many people… I got out of the subway, I got in again, and managed to go to work… I said to myself, It’s bound to happen once. Now it’s done, it’s gonna be okay.” It wasn’t. Sleep vanished. “It took me a while to accept that I was a victim… being sleep deprived, and realizing I didn’t have full control over my brain.” By late December he was in twice-weekly therapy and on sleep medication. Nine months later, September 2016, he could enter a concert hall again—cautiously, checking exits, but unafraid.

Yet the journey was not just about healing; it was about purpose. “I did not question it as a miracle. I took it as sheer luck… they always talk about survivor’s guilt, but to me, that’s a bad translation… What I experienced was more survivor’s responsibility.” That responsibility pulled him into Life for Paris, where he rose to president and gave voice to the silenced. He refused media exposure—until the 2021–2022 trial. “If I didn’t want it to be the trial only of the terrorists, I had to give some of myself… some kind of incarnation.”

As president, he took on one cause that still haunts him: the French children in Syrian camps. Most were taken there as toddlers or infants by parents who left France to join the caliphate; a smaller number were born in ISIS territory to those same parents. All are French citizens by law. None chose to go. France repatriated them in dribs and drabs—often only orphans—leaving the rest in Kurdish-run camps like al-Hol and Roj amid malnutrition, disease, sexual violence, and recruitment by lingering ISIS cells. Arthur declared them “victims just like we are,” a stance that shifted the national conversation.

The decade since the attack has been a tapestry of progress and pain. Arthur critiques France’s response to Islamic radicalization, noting the failure to address why young people—often second- or third-generation immigrants—feel disconnected from the Republic. “Why does the melting pot not seem attractive?” he asks, pointing to a political discourse stuck in platitudes, but seemingly uninterested in finding real answers as to France’s issues with parallel societies. The 2021–2022 trial, while thorough, was a grueling revisitation of trauma: “You are here in a courtroom, on a December afternoon, looking at phone reports from suspected terrorists… what am I doing here? Why am I inflicting that on myself?” Yet the overload helped: “You get bored of it… I can’t wait to not be involved with anything linked to November the 13th.”

In a bold move—a move that surprised more than a few people—he is dissolving Life for Paris. “It’s a golden cage we’ve created. It’s been useful, yes. But we can’t say at the same time, I don’t want to be a victim, and keep that association alive.” He wants survivors to transition, not marinate.

Today, as a father of three (six, four, and two), Arthur finds meaning in the everyday. “Every day, I feel grateful to be alive… I really feel lucky, grateful and I feel responsible for doing something that matters.” Raising his kids, writing his book Vivre après le Bataclan (released October 9, 2025), and advocating for change are acts of defiance against despair. He dreams of a world where his great-grandchildren know him not as a victim but as a man who, struck by history, chose to act. “Anybody can try and make a difference. And that’s worth trying… Never let the powers make you believe that you can be crushed. At least try not to be.”

As the 10th anniversary looms, Arthur’s story cuts through the noise of a fractured world. It is the tale of an ordinary man who crawled across the dying to reach the living, who turned panic into purpose, who spoke for the voiceless—including children marooned in desert camps—and who now chooses to close the door on victimhood rather than let it define him. In his refusal to be crushed, in his daily gratitude and deliberate action, we see not just survival, but defiance. A reminder that history may strike without warning, but what we do afterward is ours to decide.

*All photos, unless otherwise noted were taken by me in Paris in 2015. I had them artistically rendered out of respect for the individuals in the photos and out of respect for the time that has passed since this tragic event.

*Special thanks to Virgile Demoustier who professionally and generously helped me with a series of projects in Paris and Brussels a few weeks ago, including setting up this interview with Arthur. In addition to his professional skills, Virgile is someone who is very much worth knowing. You can find him at: www.fabfixers.com