By Philip C. Johnson—October 3, 2025

Nearly ten years ago, I was in Paris on November 13, 2015, waiting for a student group to arrive the next morning. That night, ISIS launched coordinated suicide bombings and shootings across the city—hitting the Bataclan concert hall, nearby cafes, and the Stade de France during a France-Germany soccer match. The attacks killed 130 people and injured 413, making it France’s deadliest terrorist strike since World War II. I’ve returned to Paris many times since, but this trip to Paris and Brussels forced me to confront the hidden networks behind it. In enclaves like Molenbeek and Saint-Denis, I explored not just that tragedy, but Europe’s ongoing struggle with division and renewal.

A Walk Through the Enclave

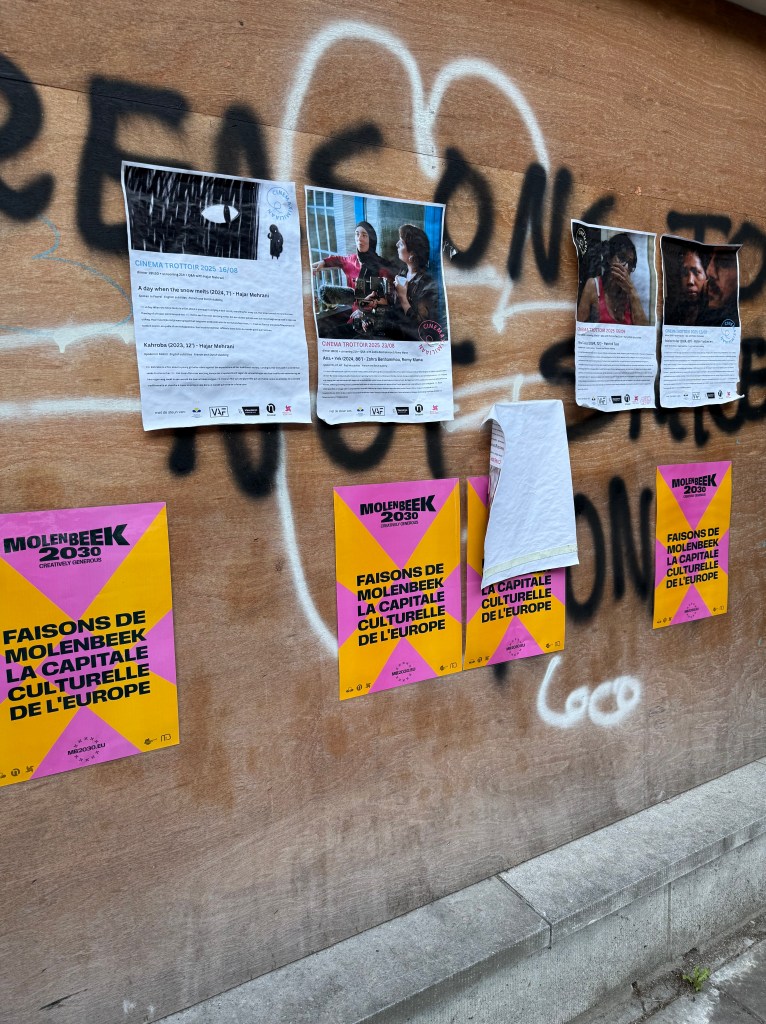

This week, I strolled Molenbeek-Saint-Jean’s narrow, crowded streets, a quick metro ride from Brussels’ shiny EU headquarters. The air buzzed with Arabic, French, and Dutch. Women in hijabs pushed strollers by halal butchers and graffiti-covered walls. Home to about 98,000-100,000 people, this dense Brussels commune has a dark reputation as “Europe’s jihadist capital.” It served as a recruitment and operations hub for ISIS-linked networks. Yet Molenbeek could be a ticking bomb or a place reborn.

The neighborhood’s push to rebrand itself highlights this divide. It joined Belgium’s bid for the European Capital of Culture 2030, promoting multiculturalism despite worries about radicalization and isolation. In the 2010s and early 2020s, reports and security experts flagged Molenbeek as a key recruitment spot. Belgium sent one of Europe’s highest per-capita shares of fighters to Syria and Iraq, with dozens—maybe hundreds—from Molenbeek and nearby areas. Its tight alleys and anonymous apartments hid weapons and fugitives, making it a base for plots across borders.

The ISIS Cell: Architects of Terror

A key case is the ISIS cell run by Abdelhamid Abaaoud, the Paris attacks’ mastermind. This 28-year-old Belgian-Moroccan from Molenbeek, nicknamed “Abu Omar al-Baljiki” for his beheading videos, was a small-time crook who climbed ISIS ranks after heading to Syria in 2013. Intelligence thought he was stuck in Raqqa; his family even mourned him as dead. But he slipped back to Europe weeks before the attacks via migrant paths—an intelligence failure like finding Osama bin Laden in New York post-9/11. It exposed weak borders and ISIS’s reach. From Molenbeek safe houses, Abaaoud managed arms from the Balkans, built suicide vests, and snuck attackers over the open French-Belgian border. His group included the El Bakraoui brothers, who later hit Brussels Airport.

Salah Abdeslam, the cell’s logistics helper, was a Molenbeek mechanic and drug dealer who joined around 2014. That night, he drove bombers to the Bataclan and Stade de France, then panicked, dumped his vest, and fled to Molenbeek. Relatives and supporters hid him, blocking police, as he dodged Europe’s biggest manhunt for 126 days.

Capture and Trials: Justice in the Aftermath

Days ago in Brussels, I paused outside 79 Rue des Quatre-Vents in Molenbeek—the dingy flat where, on March 18, 2016, police raided after spotting a suspicious white Renault. It turned into a shootout: Abdeslam and two others injured four officers before giving up. “I’m Salah Abdeslam! Don’t kill me!” he shouted, ending it without further casualties. Sent to France, he stood trial in 2022 with 19 others in the epic “Trial of the Century,” getting life without parole.

Abaaoud, the Paris event’s mastermind, never returned to Molenbeek. In Paris, I visited scarred Saint-Denis streets, stopping at the rebuilt 8 Rue du Corbillon in this gritty suburb north of the city on metro line 13. On November 18, 2015, over 100 RAID commandos raided at dawn, sparking chaos. Abaaoud fired an AK-47 and died in a stairwell shootout; another bomber blew himself up. His cousin Hasna Aitboulahcen exploded in the blast—first thought a female suicide bomber, but later clarified as accidental; her body was destroyed. Five arrests followed, including the landlord who housed them, knowingly or not. The raid hurt thirteen officers (by gunfire or explosions) and one civilian, revealing Saint-Denis’s cracks: 32% foreign-born, 20-30% Muslim, with poverty and isolation like Molenbeek’s, breeding “parallel societies.”

Molenbeek and Saint-Denis: Mirror Images

These hideouts reflect Europe’s deeper woes. Both pack North African and Sub-Saharan migrants near key transit lines, yet seem far from city centers. Molenbeek’s Muslim population is 40-45% (about 38,000-43,000), with youth near 60% and over half of Brussels’ kids Muslim. Saint-Denis matches: 20-30% Muslim, schools at 25% and climbing, poverty hovering between 28-33%. These stats drive self-segregated zones where some suggest informal Sharia courts settle a large number of family cases, gender rules dominate, and Salafists police against alcohol or mixed groups.

Radicalization’s Roots: Fault Lines of Assimilation

Jihadism grows in this mix of pipelines and neglect. Young people without jobs slide from gangs to ISIS online lures—gamified ads and secret Telegram chats hooking kids as young as 12. Molenbeek sent approximately 30-50 fighters from 2011-2018, Belgium’s worst rate. But roots dig deeper: communities resist blending, holding tribal ways, while Belgium and France falter. Austerity slashed services, leaving madrasas unchecked and police slowed by language gaps and distrust. De-radicalization efforts failed under budget cuts, as threats went digital. A February 2025 CTC report warned of “teenage terrorists” grabbing 1,700+ jihadi videos. Blame is divided: enclaves block cops, states dump integration on skimpy programs, overlooking identity clashes in Muslim-majority schools (50%+ under-18s). A late-September 2025 European Parliament conference on youth radicalization echoed this, highlighting Molenbeek’s online links to ISIS holdouts and urging more EU aid to fight youth divides.

Cultural Ambitions: The 2030 Bid and MolenFest Backlash

Molenbeek’s cultural shift seems bold but risky. Its “Molenbeek for Brussels 2030” bid sought to flip the “jihadi central” label into a diversity win. But on September 24, 2025, jurors chose Leuven, citing poverty and radical risks as feasibility barriers. Earlier, MolenFest 2025 (September 3-7) packed streets with dance, circus, music, and art for “diverse multiculturalism,” drawing crowds. Critics panned themes like “Jihad for Love” and “Sadaka” (charity with Islamic ties), timed near the November Bataclan anniversary. French MEPs called it inflammatory, boosted by a viral video of acting mayor Saliha Raïss—a veiled official—telling headscarf critics to “move elsewhere.”

Europe’s Test: Weaving Fractured Threads

Standing in front of 79 Rue des Quatre-Vents—now a plain apartment building—I sensed the shadow: everyday doors once concealed horror. In Molenbeek’s lanes and Saint-Denis markets, life persists: children play near prayer mats, elders share migration stories. Mosques run tolerance classes; small integration projects succeed. But these steps often dodge true assimilation, letting parallel worlds fester and spark backlash. Far-right figures like France’s Éric Zemmour and Belgium’s Vlaams Belang demand “remigration”—sending back non-integrated migrants and relatives—to guard culture. Others see divine sparks in those faces, calling for empathy in the fray.

At the moment, harmony seems far away. Europol’s 2025 Terrorism Report reveals the threat: 289 EU jihadist arrests in 2024, with 58 in France, 25 in Belgium—over a third under 20, plots foiled at sites like the Paris Olympics. Digital webs target 12-year-olds, mixing ideology with loneliness and mental strain. Molenbeek holds up a mirror to all of Europe: fractured threads must be mended before embers reignite. The 2025 arrest reports and foiled plots demand action—bolstered policing, funded integration, community bridges—before the next shadow falls.

The snub aligned with the Parliament conference, stressing Molenbeek’s online ISIS ties. On X, users called it a “terror hotbed” beyond Dearborn’s, fearing “jihad exports” amid Brussels gang spikes. No big 2025 attacks have struck, but threats simmered: a September 26 firing of a Flemish Islam teacher over extremist books showed the edge.

Phil Johnson in Brussels, Belgium, September 2025

Meanwhile most citizens of these cities are either oblivious or too afraid to force leaders to truly address the threat. In this age of tolerance we are risking our freedom and safety.